I’m grateful to the New York Times Magazine for the confidence they showed in assigning this story, Gold Mania in the Yukon, about Shawn Ryan and Cathy Wood, whose discoveries launched a new Klondike stampede. On the surface, a classic tale of pluck and luck. Shawn and Cathy used some big changes in the world around them to solve a mystery that had been around for more than 100 years: where did the great placer deposits of the Klondike gold rush come from? Two isolated prospectors, who started out picking wild mushrooms for cash in the burned forests around Dawson City, find evidence of gold worth billions of dollars.

Gold is a strange commodity. We think of it as inherently valuable, but its value rises and falls like any product. Ryan and Wood, at the crucial turning point in their story, realize that the gold market is just like the market for wild mushrooms. In both cases, something found just sitting there in the ground is convertible into cash. That’s nature’s bounty. But actually making this transaction requires participation in a crazy commercial network, with immense risk.

In one of the most famous polemics ever written, the contageous turmoil of market economies is described like this:

Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real condition of life and his relations with his kind.

That’s Karl Marx, of course. And yet the thing that makes gold different from mushrooms, and from all other commodities, is that gold actually signifies safety, protection from risk. Underlying my story is this contradiction.

Writing about Shawn and Cathy’s discovery made me ask myself: if gold can’t really protect us, what can? While my piece is a story about gold, it is also a story about a marriage, love, partnership, and about the fragile miracles of cooperation that allow us to accomplish difficult things. Although I enjoy being a magazine writer, I suspect that the full dimensions of this story ultimately requires a format more sympathetic to melodrama. The 24 hour summer sun and the dark winter noontimes, the flow of water (and of snow in that fatal avalanche), the almost musical boasting and gossiping; these could be a kind of stage for the contradictory desires associated with both gold and love.

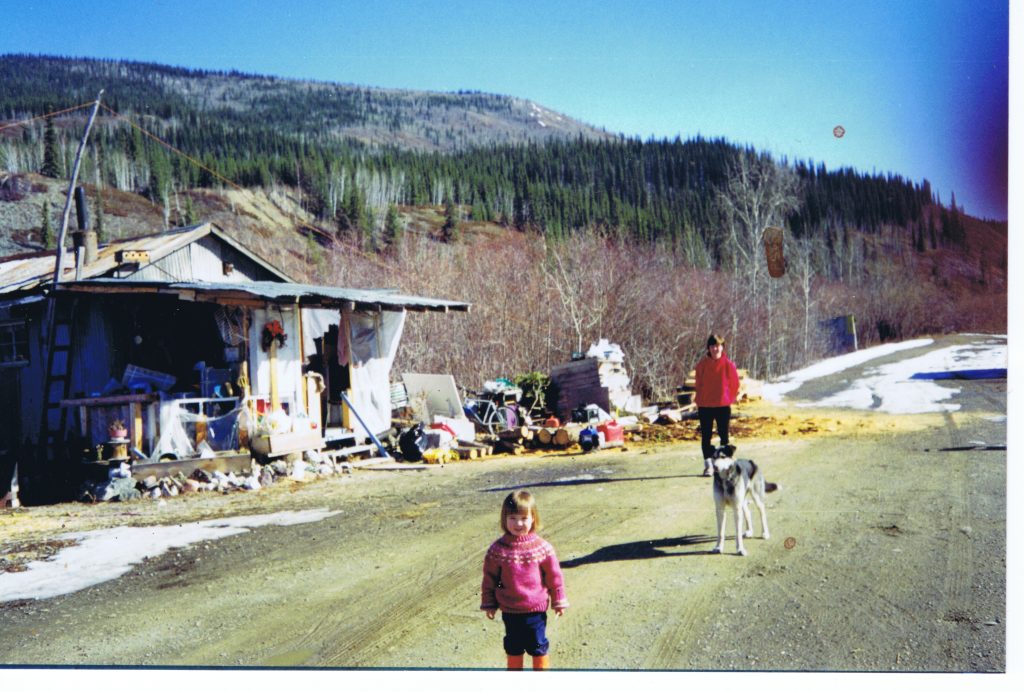

Below are a few snapshots and captions that track my reporting.

As you cross into the Yukon by air, you notice that the roads disappear.

In California the hippies have VW vans. In the Yukon they have old fixed wing aircraft.

Whitehorse, the territorial capital, has about 20,000 people. The Yukon covers nearly 500,000 square kilometers, most of it nearly unpopulated.

Our small plane into the staking camp slowly puttered over the mountains at about 100 mph. It felt like traveling in a kite, but louder.

A frozen lake makes a handy airfield.

A little Ski-doo is light enough to throw onto a plane and take into the field. Shawn uses it to ferry supplies.

The guys out at the staking camp live in a tent with a wood stove. They try not to let the stove go out.

This view of the interior of the tent reminded me of old photos of miners.

The stakes in the foreground are used to mark claims.The barrels contain fuel.

The small orange dot in the upper center of the picture is a stake. The line in the snow is made by the snowshoes of the man who put in the stake.

Another track made by a man staking claims.

Information about exploration plans is exchanged and concealed through seemingly casual conversation, as in a poker game.

We didn’t really take that hippie aircraft. Our vehicle was a Maule M-7-235 on skis. I asked the pilot how long we had to go before we saw any sign of human habitation. “If you miss Santa Claus’ house, then Europe,” he said.